Frontotemporal Dementia

What is frontotemporal dementia?

A neurodegenerative disease causing tissue shrinkage and reduced function in the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is thought to account for 10-15% of dementia cases. It accounts for roughly 20% of early-onset dementia cases, general displaying its first symptoms between the ages of 55 and 65. The disease appears to affect men and women at equal rates.

The areas of the brain damaged by frontotemporal dementia are responsible for attention, planning and motivation (frontal lobe) as well as visual memories, processing sensory input, understanding language, storing recent memories, emotions and deriving meaning (temporal lobe). As with most dementias, the mechanism causing the cell damage leading to frontotemporal dementia is little-understood.

Because FTD often occurs in people in their 40s and 50s its effect on families can be devastating. Because the disease strikes during many patients’ top wage-earning years, the financial effects can be extreme. Patients may also still have children living in the home.

Symptoms & Diagnosis of Frontotemporal Dementia

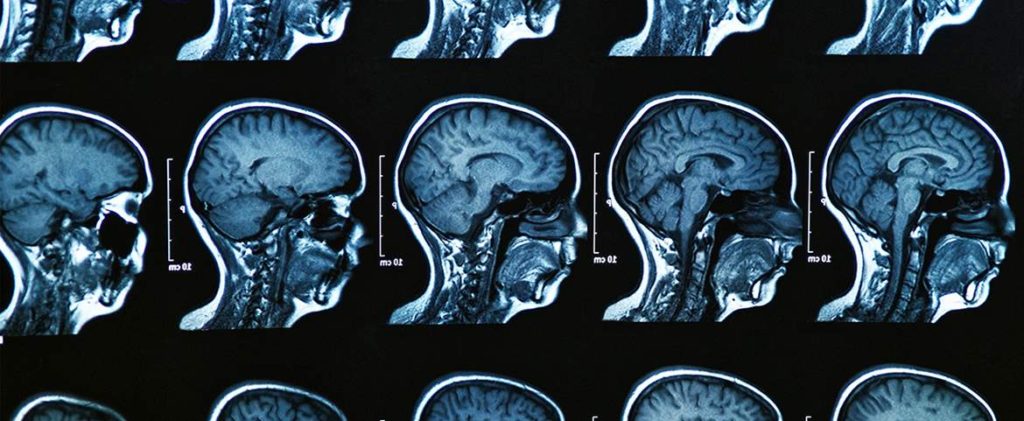

Frontotemporal dementia can commonly be broken into three main categories, the differentiation in symptoms based on the regions of the brain affected by deterioration. As the disease progresses and other areas are affected the symptoms overlap into a more generalized set of symptoms. No tests can conclusively diagnose frontotemporal dementia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET imaging can help with diagnosis by detecting shrinkage in the frontal and temporal lobes, but FTD is a “clinical” diagnosis made from a doctor’s best judgment about the evidence at hand.

The three types of frontotemporal dementia are defined as follows:

- Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD)

This variant predominantly affects the patient’s personality and behavior. Often mistaken for depression due to the subtle way in which symptoms can appear, this type of the disease develops into a lack of inhibition and extreme deficiencies of restraint in personal and social relationships. - Primary progressive aphasia (PPA)

Language skills are the key areas affected in the early stages of this form of the disease, though it has been known to affect behavior as it progresses. PPA has two different subcategories based on how the symptoms manifest:- Semantic dementia: Physical ability to speak suffers little, but word choice becomes limited and meaning can be difficult to discern. The use of specific words may become difficult, leading to the use of broader terms (“food” instead of “sandwich”). A patient’s ability to comprehend words spoken to them may also be affected.

- Progressive nonfluent aphasia: The act of speaking becomes more difficult and words become difficult to find, leading to a way of speaking that seems faltering, as though the patient is “tongue-tied”. Grammar, reading and writing may also be affected.

- Frontotemporal dementia movement disorders

Certain involuntary, automatic muscle functions can be affected by this form of the disease, which has two variations. In addition to muscle and movement problems, FTD movement disorders have also shown to impair language and behavior.- Corticobasal degeneration (CBD): Causes tremors, lack of coordination, and muscle rigidity/spasms.

- Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP): Causes problems with walking and balance (leading to frequent falls), muscle stiffness (mainly in the neck and upper body) and issues with eye movement.

Frontotemporal Dementia Treatment

As with all dementias, there is no way to “cure,” reverse or stop the damage caused by frontotemporal dementia. Current treatments focus on managing the disease’s behavioral symptoms and keep patients as functional and comfortable as possible. Various drugs and caregiving techniques have been shown to help reduce certain symptoms, though nothing has proven to stop the progression of the disease.